GoldenEye and The Prisoner: Victims of Fashion

GoldenEye (1995) is the best Bond film in the franchise’s history.

At least that’s how this essay may have started in a slightly different timeline—with apologies for the clickbait opening.

GoldenEye marks Pierce Brosnan’s long-delayed introduction as James Bond. It is undoubtedly his best Bond film and is widely regarded as one of the stronger entries in the series, currently sitting at number ten on Rotten Tomatoes’ ranking of Bond films.

None of this should be surprising since GoldenEye has so many things working in its favor.

From the stars to the recognizable character actors, the cast delivers. Brosnan reinvigorates the franchise with the look, bearing, charm, and physicality demanded of the role. Sean Bean brings a personal gravitas to the antagonist, Famke Janssen is just delightfully unhinged, Judi Dench’s M provides Bond with an internal obstacle he has to navigate, and “Bond girl” Izabella Scorupco is one of the most unique in the canon.

The action set pieces are iconic and visceral: the opening dam jump, the tank chase, and the final showdown all linger in the memory.

Most importantly, the script is one of the strongest in the entire series, particularly given everything it is asked to accomplish. After a six-year absence, GoldenEye has to bring Bond into the 1990s and integrate him into a world that reflects changing allegiances brought on by the collapse of the Iron Curtain. It succeeds through smart writing that combines Cold War symbolism and strong characters. General Ourumov and arms dealer Janus keep the Cold War mythology intact while acknowledging its disintegration; this is Bond proving that he is still relevant in this transitional world.

The screenplay also finds a way to incorporate the franchise’s camp without spilling over into the entire film. The campy excesses are isolated almost entirely within the wonderfully cartoonish Xenia character. It’s a brilliant decision that allows the film to indulge in the over-the-top fun while keeping the rest of the movie grounded and credible.

And there is Natalya Simonova, who may be the most fully realized character in the series. She is never objectified, consistently challenges Bond, and possesses genuine agency. Her relationship with Bond is not that of seductress or prey but is instead something reciprocal, meaningful, and earned.

And because the casting and screenplay’s sophisticated reinvention are done so well, the film’s one failure matters. And that failure is the score.

Éric Serra’s industrial euro-thriller score has been polarizing since the film’s release, and as an admirer of film music, it pains me to identify this as GoldenEye’s one crucial flaw.

This isn’t a direct commentary on the music as music but is indicative that, on the whole, Serra’s music is ill-suited to the needs of the film.

The score begins with promise, with the opening cues over the infiltration of the weapon’s plant working extremely well. Starting with delicate percussion, heavier synth, and echoes of the Bond theme played on timpani. Multiple layers of synth and percussion move in and out while some bluesy synth sounds make an appearance from time to time. The rhythmic mechanical sound reflects the operational precision of the mission while providing an underlying and escalating tension. This works very well.

As Bond makes his escape, we get forceful percussion with fragments of the Bond theme played on different synths and registers, some of them suggesting the brassy Bond sound but again augmented for synth. As the scene progresses and Bond’s predicament worsens, the intensity doesn’t increase, with the exception of the addition of a Russian-sounding male chorus. 007 pulls the plane out of a dive and flies by the exploding weapons factory as Bono and The Edge’s retro-sounding GoldenEye song starts, and, notably, the emotional intensity immediately increases.

The next musical cue is “Ladies First,” where Bond and Xenia push their cars to the limit (and beyond!) on winding roads while engaging in a flirtatious game of cat and mouse. The scene demands playful danger and seductive energy, but what Serra delivers here can best be described as a very 1990s combination of DJ scratching, jazzy hip hop, and avant-garde pop. Even defenders of Serra’s score are hard-pressed to put a positive spin on this cue.

The very next scene is the (obligatory?) casino sequence—a moment that functions as a deliberate mirror of Bond’s introduction in Dr. No. In Dr. No, Bond is the dealer and rises from the table first, while in GoldenEye, Xenia deals the cards while deciding to leave the table ahead of Bond. Even the camera work is similar, following the woman until Bond eventually rejoins the frame.

This mirroring of the scenes is extended to the music, but the reversal removes what made the original scene effective. In Dr. No, the casino scene plays entirely without score until Bond delivers the now famous line, “Bond. James Bond.” The music comes in at just the right moment to emphasize Connery’s swagger and confidence. In GoldenEye, Éric Serra’s romantic theme begins even as Bond drives up to the casino and continues through the scene itself.

The romantic theme might seem to be a bit too much given that there hasn’t been any romance shown (or even hinted at), but my objection is not about the music per se but that its very presence undermines the scene’s purpose. The scene is built around sexual tension, witty dialogue, and verbal sparring. All of which are enhanced by the relative silence, the rhythm of the dialogue, and the murmur of the crowd. A side-by-side comparison demonstrates how Dr. No’s less-is-more approach can make for a better scene. GoldenEye, however, instead opts for a denser, more modern scoring approach. Whether this was a directorial choice, a producer's input, or Serra's instinct, the result is what matters—and what's on screen undermines what the scene requires.

There’s one more category of music that reappears throughout the film: action music. In most instances, Serra falls back to variations of the style he used in the opening scene but with more obvious Bond stylizations layered on. These cues are not bad, but they lack the energy and excitement that a more direct orchestral approach would provide. And we don’t have to guess about this because the tank chase provides all of the evidence. The tank chase is the big set piece of the film and probably its most memorable moment. Sure, the image of a tank destroying St. Petersburg leaves an impression, but the bigger impact hits from the replacement cue written by John Altman. This is the moment where GoldenEye truly comes alive and proves how good it can be. The traditional Bond scoring elements are there—the brass, the strings, and the vocabulary—but Serra-influenced percussion and pounding low piano are still included, showing how well a hybrid approach could have worked throughout.

At the end of the 1980s, it appeared that the Bond franchise may have run its course. Competition from 1980s action movies and the emergence of other action stars had cut into Bond’s cultural cachet as well as box office; 1987’s The Living Daylights and 1989’s Licence to Kill are, to this day, the lowest-grossing Bond films after adjusting for inflation. Production was delayed due to lawsuits involving the sale of rights, contributing to the six-year delay between Bond films. In the meantime, the global political landscape underwent massive changes: the fall of the Berlin Wall followed by German reunification and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent end of the Cold War.

With this context, it’s easy to imagine what happened. The series of lower box office results made it obvious that whatever the Bond series was doing wasn’t working and that a reinvention was necessary. This started with an entirely new actor to play Bond, but the theme of change reflecting this new era informs the entire script: the new M being a woman—an obstacle character that even names Bond as a “dinosaur,” a villain named Janus, the god of thresholds and transitions, and a Russia that is internally out of control.

Although the job of scoring GoldenEye was originally offered to John Barry (who declined), it was clear that the production team wanted a new direction. And what was the hot, modern sound of the early to mid-1990s? It was Éric Serra, the composer of choice of Luc Besson.

Serra in 1995 was not a new commodity—he had been scoring films since the early 1980s—and, with one exception, Luc Besson directed all of those films. Although not commonly recognized, this is arguably one of the longest and most successful director/composer pairings in cinema history.

No doubt the main scores that brought Serra to the producers’ attention were La Femme Nikita (1990) and Léon: The Professional (1994), Besson’s English-language debut. Both films are stylish thrillers with assassins, and Serra received nominations for Best Music Césars (France’s equivalent of the Oscar) in both of them. Both films also showcase a European flair and modern musical style that seems like a perfect fit for what the producers might hope to replicate in GoldenEye.

The titular characters in Nikita and Léon are both broken people. The former, a drug-addled murderer with anger issues, is repurposed as a cold-blooded government assassin, while the latter is a simple, naive man who, despite being a violent killer, possesses a childlike innocence. Both scores tend to have two broad approaches: cold percussion and synths for the thriller scenes and tragic strings underscoring the emotional moments. It’s a cold soundscape, with even the strings not revealing excessive warmth. It works perfectly, reflecting the isolation and tragic story of the characters while enhancing the on-screen action and tension. Overall, it’s a fairly straightforward approach, with the music generally reflecting what’s on screen; the main variation is to dial back the tension in order to emphasize the tragedy (e.g., less percussion and more strings).

The mismatch here is that Brosnan’s Bond is not cold; yes, he’s calculating and composed, but he’s also witty and passionate. Serra’s score never addresses or enhances these aspects of the character. The deeper limitation, however, is systemic: Serra’s default mode is to address what is directly on the screen rather than performing the more important functions in a Bond film—serving the characters, enhancing subtext, and supporting the overall themes.

Take, for example, the beginning of the final showdown. Bond and Natalya escape out of the lair and back outside to the satellite dish. As Bond runs off to disable the transmitter, Serra contributes a short synth pad before fading out. The next scene of Alec and Boris dealing with the aftermath of the earlier explosion plays completely unscored. As a thought experiment, let's examine what this scene becomes when we introduce part of the Bond theme.

This version instantly builds excitement and also signals to the audience that Bond is coming, he’s reasserting control, and that order is about to be restored. After cutting to the control center, the music continues, adding Bond’s presence and reframing the entire moment into a personal confrontation rather than general chaos; Alec’s mounting dread is no longer about the fire and failing satellite—it’s now about Bond. This is mythic alignment, where the music provides pure emotion while communicating more than the visuals alone ever could.

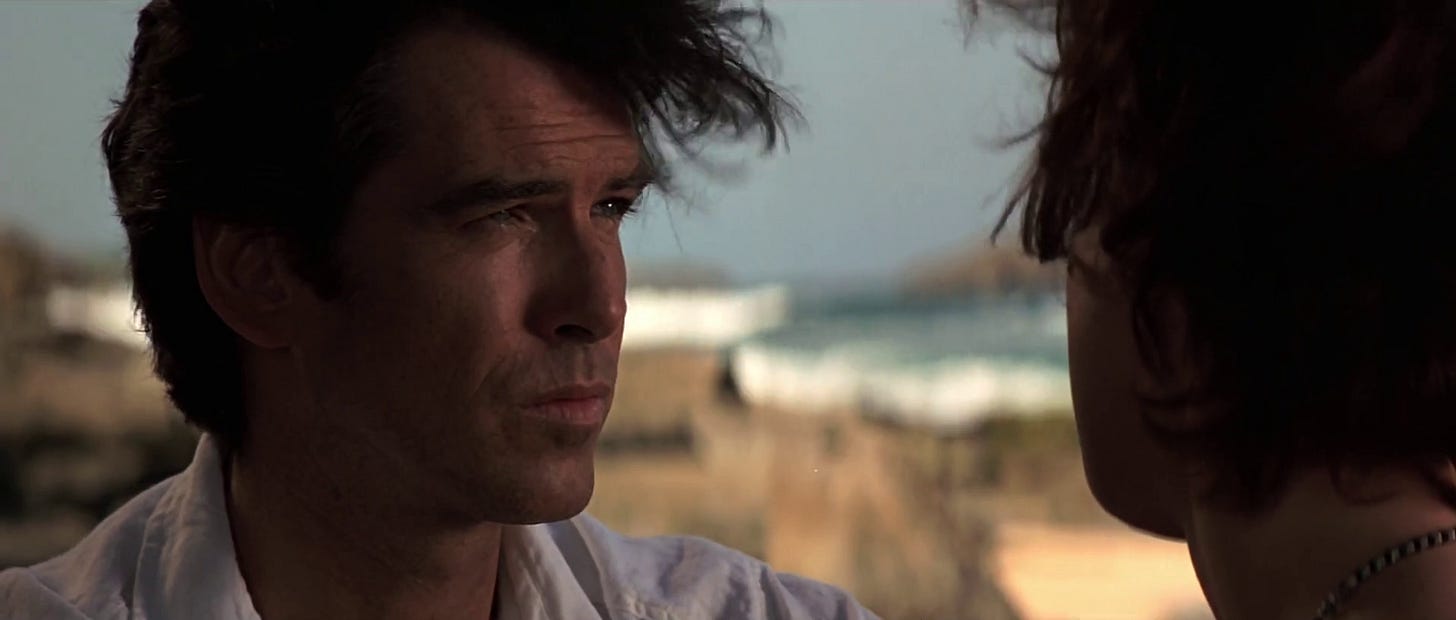

All of this isn’t to simply criticize Serra—sometimes the score works. For example, the style is ideal for moments of isolation and defeat. After escaping Alec, alone on the beach with Natalya, when Bond is at his nadir, Serra’s score perfectly captures the character’s internal fracture. The love theme here is tender, wistful, full of heartache and regret, and perfectly matched to the scene. However, Bond as a character also needs the score to demonstrate resilience, humor, romance, and power—something Serra fails to do consistently.

The story of GoldenEye isn't unique. Nearly thirty years earlier, another artist creating a classic spy story made a strikingly similar choice: prioritize fashionable aesthetics over what their material actually required. That artist was Patrick McGoohan, and his project was The Prisoner (1967).

McGoohan’s The Prisoner is a cult classic that initially presents itself as a 1960s spy thriller—perhaps a continuation of Danger Man. But as the series plays out, it reveals itself to also be a Kafkaesque philosophical inquiry into the relationship between the individual and society. The beauty is that it can be enjoyed on multiple levels: pure spy thriller or allegorical commentary. It may sound hyperbolic, but television had never seen anything quite like The Prisoner.

The typical tone of The Prisoner involves light surrealism, a dose of paranoia, and (bureaucratic, social, and individual) pressure, all in service of breaking Number Six. The show is deadly serious even when invoking strange mind control or other sci-fi psychological oddities. However, the final episode, Fall Out, abandons this entirely and switches to a very 1960s surrealistic and psychedelic style. It’s not an escalation; it’s a full seismic tonal shift: Beatles songs, a mod character spouting 1960s slang and chanting “Dem Bones,” and a trial that is more farce than mythic confrontation (among other chaos). To be honest, it’s hard to give the anarchy visible on screen justice using the written word.

This sudden tonal shift is not necessarily a bad thing. The pertinent question is, does it serve the underlying themes and the intended message of the show? And, yes, The Prisoner has some important ideas to convey: the nature of freedom and the nature of the prison—a person, place, or state of mind? The reveal of Number Six as Number One is a bold and subversive idea. The cavern as the location for most of the episode can work as a symbol of the descent into the underworld (of the self). A trial with a chorus could be an interesting exploration of the individual versus the group. These aren’t problems. And the problem isn’t that the show has dated itself to the 1960s, either. The root problem is that the execution and tone of Fall Out are so at odds with the rest of the series that the ideas in the show are overwhelmed. The style and form are so distracting that the substance is lost; instead of processing the message, the audience is processing the form.

To me, it appears that when Patrick McGoohan was writing the finale, he wanted to incorporate the ideas of revolt and rebellion. On a deadline, he reached for the current representation of those ideas: 1960s counterculture and its dominant aesthetic of surrealism and psychedelia. On some level, this makes perfect sense, but The Prisoner didn’t need to cloak the finale in 1960s visual rebellion to communicate actual rebellion—that was already part of the show’s DNA.

Here we have GoldenEye and The Prisoner, a movie and a television show made over a quarter of a century apart, making similar decisions. Both are successful in achieving their vision but are held back by one major issue: when reaching for something new, both of them embraced the fashion of the day without considering or questioning whether that was the right aesthetic for their specific project. Hindsight is twenty-twenty, of course, and perhaps they did consider this, but in the moment, and under time pressure, they couldn’t see the issues immediately. Although in the case of GoldenEye, the issue was at least attempted to be corrected with the replacement of the cue for the tank chase. The composer of that cue, John Altman, has said that the producers told him, “We’d have given you the whole film to re-score if we’d known you were that quick,” which, if true, is very telling about their opinion of Serra’s score. McGoohan, on the other hand, never, to my knowledge, indicated any regret about the ending that he wrote. It’s possible that he genuinely thought it worked well, or maybe he valued confounding the audience more than serving the material to the highest degree possible.

But there’s another factor to consider as well. We all like to imagine the auteur, the lone creator with the singular vision, as a driving force, but maybe this force needs to be tamed occasionally? Part of the issue with GoldenEye is that Serra had only ever worked with Besson in a very specific way: Besson would come up with the emotion of the scene he wanted, Serra would write the music, and Besson would have daily check-ins. However, with GoldenEye, it sounds like Serra, working on his first Hollywood movie at the same time as working with new people using a different process, was given free rein with little supervision. He may have been getting so many notes from different parties (according to Altman) that he insulated himself from this feedback as much as possible. Some institutional oversight may have worked wonders for Serra’s score. Likewise, McGoohan could probably have used some pushback from someone (perhaps George Markstein, the series' script editor and disputed co-creator) to challenge his script ideas.

Because their foundations are so strong, both GoldenEye and The Prisoner survive their missteps and remain iconic despite their flaws. They also serve as cautionary tales: fashion is seductive precisely because it feels contemporary and right in the moment. But recognizing the gap between what the material requires versus what seems exciting and new may be the hardest part of the creative process.

Not all great films are equally great. Subscribe to Cinemyth to understand the structural and mythic principles that separate masterpieces from near-misses.